Why Open Source Is the Key to Technological Progress

The code running your life is mostly free. The Linux kernel powers your Android phone, your smart TV, most web servers, and the world’s supercomputers. The React framework renders billions of web pages. PostgreSQL stores critical data for companies worth trillions. TensorFlow and PyTorch enable AI systems that are reshaping industries.

None of this software was purchased. It was given away—source code visible to anyone, modifiable by anyone, usable by anyone for any purpose. The most important infrastructure of the digital age was built by volunteers, hobbyists, and companies that chose to share rather than hoard.

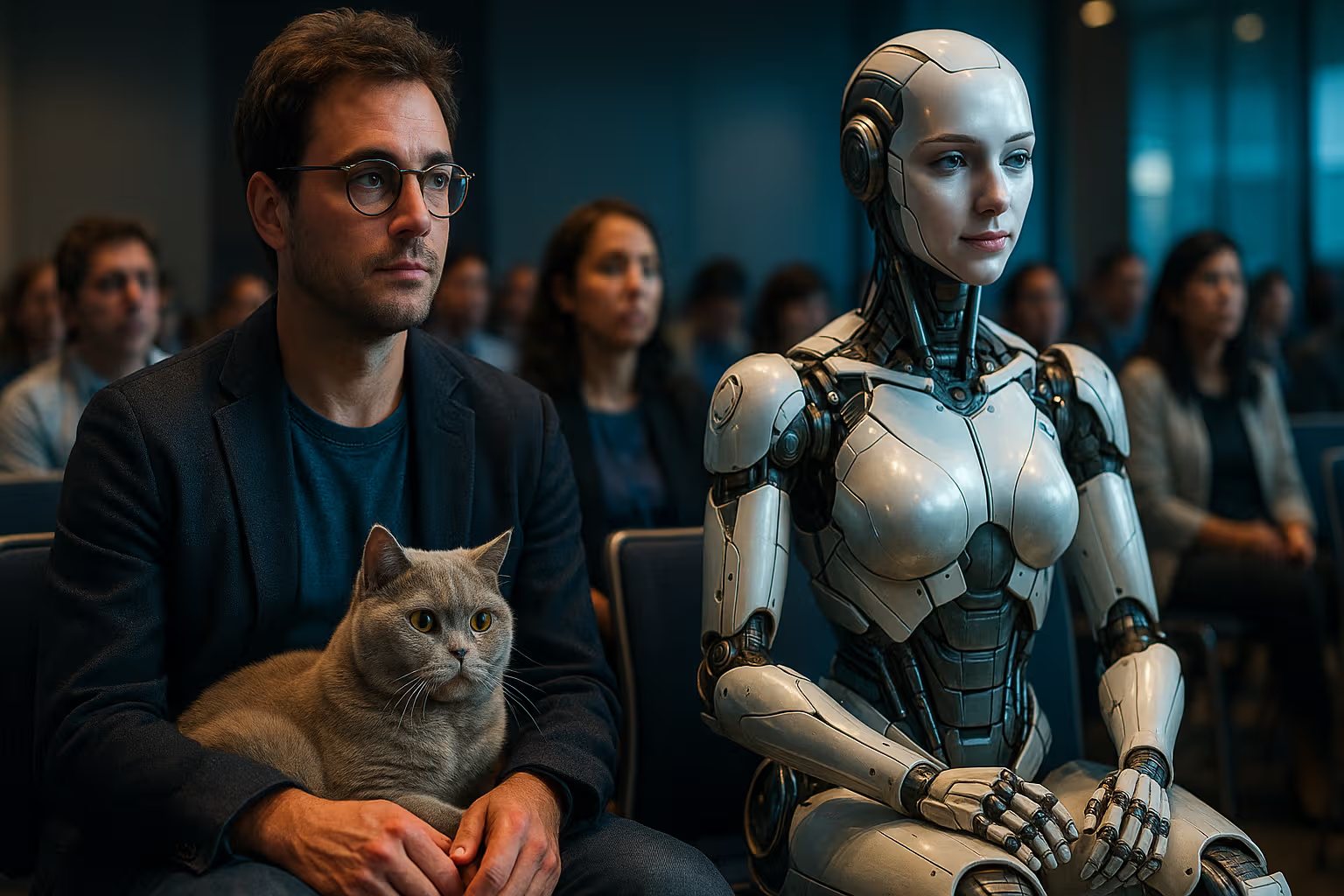

My British lilac cat, Mochi, operates on proprietary biological software—her genome is not open source. But even she benefits from open source: the automated feeder that dispenses her meals runs Linux. The smart home that controls her environment uses open-source protocols. The veterinary systems that manage her health records run on open-source databases.

This article examines why open source has become the dominant model for technological progress. Not as ideology but as practical strategy. The question isn’t whether open source is morally superior—it’s why open source consistently outcompetes closed alternatives in building the foundational technologies of our time.

Understanding this dynamic matters for anyone building technology, investing in technology, or simply trying to understand how the digital world actually works.

The Paradox of Giving Away Value

Open source presents a puzzle: why would anyone invest effort creating something and then give it away? The economist’s model says people work for compensation. Open source seems to violate this model.

The resolution lies in understanding what open source actually gives away and what it doesn’t. The source code is free. But expertise in that code isn’t free. Integration services aren’t free. Support isn’t free. Hosted versions aren’t free. The ecosystem around free software creates substantial economic value.

The Red Hat Model

Red Hat built a billion-dollar business on Linux, software anyone can download for free. The company didn’t sell Linux—it sold certainty. Enterprises paid for tested, certified, supported versions of free software. They paid for someone to call when things broke. They paid to reduce risk.

This model proved that free software and profitable business weren’t contradictory. The software is free; the assurance costs money.

The Infrastructure Play

Companies open-source software to make it infrastructure. If everyone uses your framework, your database, your protocol, you benefit even without direct payment.

Facebook open-sourced React because widespread React adoption benefits Facebook. More React developers means easier Facebook hiring. Better React tooling benefits Facebook’s development. React becoming standard makes Facebook’s technical choices mainstream rather than idiosyncratic.

The Ecosystem Effect

Open-source projects attract contributions. External developers find bugs, add features, improve documentation. A company that open-sources a project gets free development labor—often more than it contributes itself.

The Linux kernel receives contributions from thousands of developers at hundreds of companies. No single company could afford this development effort. But collectively, through open source, they produce software that benefits everyone.

The Recruitment Funnel

Open-source contributions reveal developer capability. Companies evaluate potential hires through their open-source work. Developers build reputations through visible contributions. The open-source ecosystem functions as a massive, continuous job interview.

This recruitment value motivates both companies and individuals to participate. Companies want to be seen as open-source-friendly employers. Developers want to demonstrate skills publicly. Both incentives drive contribution.

The Innovation Advantage

Open source accelerates innovation through mechanisms closed development can’t match:

Standing on Shoulders

When you build on open-source foundations, you don’t reinvent wheels. Need a web server? Use Nginx. Need a database? Use PostgreSQL. Need machine learning? Use PyTorch. Each project represents millions of hours of development you don’t have to repeat.

This standing-on-shoulders effect compounds. Each generation of open-source projects builds on previous generations. The accumulated infrastructure becomes a platform for ever-more-ambitious projects.

Closed-source development faces a choice: build everything yourself or pay for components. Open source eliminates this choice. The best components are usually free.

Faster Bug Discovery

“Given enough eyeballs, all bugs are shallow.” Linus’s Law captures a truth about open source: public code receives public scrutiny. Security researchers examine popular open-source projects. Users report bugs. Contributors fix them.

Closed source hides bugs behind opacity. The bugs exist—hidden code isn’t bug-free code—but they’re discovered more slowly, often by attackers rather than defenders.

The OpenSSL Heartbleed bug illustrated both the vulnerability and resilience of open source. The bug existed in widely-used security software. But once discovered, it was fixed immediately, and the fix was immediately available to everyone. A comparable bug in proprietary software would require waiting for the vendor.

Fork-Driven Competition

If an open-source project goes in a direction you don’t like, you can fork it—take the code and develop it differently. This fork option disciplines project governance. Maintainers who ignore community needs risk losing their community to a fork.

Closed software offers no comparable mechanism. If a vendor makes decisions you dislike, your options are complain or leave. Open source adds: or take the code and do it better.

MySQL to MariaDB illustrates this dynamic. When Oracle acquired MySQL and the community grew concerned about its stewardship, MariaDB forked the project. The competition improved both projects.

flowchart TD

A[Open Source Project] --> B[Community Contribution]

B --> C[Bug Fixes]

B --> D[New Features]

B --> E[Documentation]

B --> F[Security Audits]

C --> G[Improved Software]

D --> G

E --> G

F --> G

G --> H[Wider Adoption]

H --> I[More Contributors]

I --> BHow We Evaluated: A Step-by-Step Method

To assess open source’s role in technological progress, I followed this methodology:

Step 1: Map the Infrastructure

I catalogued the open-source components underlying major technology systems. What runs web servers? What powers mobile operating systems? What enables cloud computing? What trains AI models?

Step 2: Trace Development History

I examined how key technologies developed. Did open-source or closed-source approaches advance faster? Where did innovation originate?

Step 3: Analyze Contribution Patterns

I studied contribution data for major projects. Who contributes? How many contributors? What’s the relationship between contribution and adoption?

Step 4: Examine Business Models

I analyzed how companies build businesses around open source. What works? What fails? What sustainable models exist?

Step 5: Survey Developer Sentiment

I reviewed surveys and research on developer attitudes toward open source. Do developers prefer working with open source? Why?

Step 6: Assess Counterfactuals

I considered alternatives. What would the technology landscape look like without open source? What innovations would not have happened?

The Infrastructure Layer

Open source dominates infrastructure—the foundational software everything else runs on:

Operating Systems

Linux powers the majority of servers, most mobile devices (through Android), virtually all supercomputers, and most embedded systems. Windows dominates desktops, but even Microsoft now embraces Linux—Azure runs more Linux than Windows VMs.

The server victory is particularly striking. When businesses choose infrastructure without consumer marketing influence, they overwhelmingly choose open source. The technical merits decide.

Web Infrastructure

Apache and Nginx serve most web traffic. Open-source programming languages—Python, JavaScript, PHP, Ruby, Go—write most web applications. Open-source databases—PostgreSQL, MySQL, MongoDB—store most web data. Open-source frameworks—React, Vue, Django, Rails—structure most web development.

The web is an open-source achievement. The proprietary alternatives that once competed—commercial web servers, proprietary application servers, closed databases—have been marginalized or open-sourced themselves.

Cloud Computing

Cloud providers build on open-source foundations. Kubernetes orchestrates containers across all major clouds. Docker (now largely open-sourced) standardized containerization. Terraform manages infrastructure. Prometheus monitors systems.

The cloud would be impossible without open source. The scale and complexity require shared infrastructure. No single company could build everything the cloud requires.

Artificial Intelligence

The AI revolution runs on open source. TensorFlow (Google), PyTorch (Meta), and other frameworks are open source. Training datasets are increasingly shared. Model architectures are published openly. Even model weights—expensive to produce—are often released.

This openness accelerates AI progress. Researchers build on each other’s work immediately. Implementations are available to everyone. The field advances faster than any closed approach could match.

The Collaboration Model

Open-source collaboration has distinctive characteristics:

Asynchronous, Global

Open-source projects coordinate contributors across time zones and continents. They work asynchronously—no meetings required. They communicate through code, issues, and documentation. This model enables participation that geographic clustering would prevent.

The Linux kernel has contributors from every inhabited continent. They’ve never all been in the same room. They collaborate through mailing lists, version control, and code review. The model works for projects of enormous complexity.

Meritocratic Review

Code contributions succeed or fail on merit. The author’s employer, credentials, and seniority matter less than the code’s quality. This meritocracy attracts talented developers who might be overlooked in corporate hierarchies.

Review processes in major projects are rigorous. Getting code into the Linux kernel requires passing multiple review stages. The scrutiny ensures quality and provides learning opportunities for contributors.

Transparent Decision-Making

Open-source decisions happen publicly. Discussions occur on mailing lists or GitHub issues. Disagreements are visible. Rationales are documented. This transparency creates accountability and enables learning.

Closed projects make decisions invisibly. Users see outcomes without understanding reasoning. Open source shows its work.

Governance Experimentation

Different projects try different governance models. Some have benevolent dictators (Linux). Some have foundations (Apache). Some have corporate sponsors (Kubernetes). Some are pure communities (Debian).

This experimentation identifies what works. Successful governance models spread. Failed models are abandoned or reformed. The ecosystem learns through variation.

flowchart LR

A[Governance Models] --> B[BDFL: Benevolent Dictator]

A --> C[Foundation: Apache, Linux Foundation]

A --> D[Corporate Sponsor: Google, Meta]

A --> E[Pure Community: Debian]

B --> F[Fast Decisions]

C --> G[Neutral Ground]

D --> H[Resources + Risk]

E --> I[Independence]The Business Reality

Open source isn’t just idealism—it’s business strategy:

Cloud Service Providers

AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud built enormous businesses partly by offering managed open-source services. They take PostgreSQL, Elasticsearch, Kubernetes and offer them as services. The software is free; the hosting and management cost money.

This model has created tension. Open-source projects see cloud providers capturing value they created. Some projects have changed licenses to restrict cloud offerings. The business model works but creates conflict.

Developer Tools Companies

Companies like GitHub, GitLab, and JetBrains build businesses serving open-source developers. GitHub hosts repositories. GitLab provides DevOps platforms. JetBrains makes IDEs. The open-source ecosystem creates demand for tooling.

These businesses depend on open source thriving. They invest in open source to sustain their markets. Microsoft’s GitHub acquisition—and subsequent investment in open source—reflects this dynamic.

Open Core

Many companies offer open-source cores with proprietary extensions. MongoDB, Elastic, and Redis follow variations of this model. The core product is open source; enterprise features require payment.

This model balances community building with revenue capture. The open core attracts users and contributors. The proprietary extensions capture value from enterprises willing to pay.

Support and Services

Red Hat pioneered the support model. Canonical (Ubuntu), SUSE, and others follow it. The software is free; professional support, training, and certification cost money.

This model works for infrastructure software that enterprises want assurance about. It works less well for software that doesn’t require ongoing support.

The Challenges

Open source isn’t without problems:

Sustainability

Many critical open-source projects are maintained by one or two people in their spare time. The Log4j vulnerability revealed that a widely-used security library had minimal maintenance resources. The infrastructure of the internet rested on volunteer labor.

Sustainability solutions are emerging—GitHub Sponsors, Open Collective, foundation support, corporate sponsorship. But many projects remain under-resourced relative to their importance.

Security

Open-source security cuts both ways. Public code enables public review—but also enables attackers to study code for vulnerabilities. The benefits of transparency require actual review. Code that’s open but unreviewed may be worse than code that’s closed but audited.

Major projects receive substantial security attention. Small projects may not. The long tail of open source includes much code that nobody reviews carefully.

Governance Conflicts

Open-source projects can fracture over governance disputes. Personality conflicts, technical disagreements, and corporate influence create tensions. Some projects implode. Others fork acrimoniously.

The Node.js/io.js split and reunion illustrates both the risk and resolution. Governance failure led to a fork. Eventually, the communities reunited under reformed governance. But the disruption was real.

Corporate Capture

Companies that dominate open-source projects can effectively control them. Google’s influence over Kubernetes, Facebook’s over React, and Oracle’s over Java raise concerns. Open source nominally, but corporate-controlled practically.

Foundations like Apache and Linux Foundation exist partly to prevent capture. They provide neutral governance that no single company controls. But corporate influence remains significant.

License Complexity

Open-source licenses vary in permissions and requirements. GPL requires sharing modifications. MIT permits anything. Apache includes patent grants. BSD variants differ in attribution requirements.

This complexity creates compliance challenges. Companies using open source must track licenses across dependencies. Legal review becomes necessary. The freedom of open source comes with administrative burden.

Generative Engine Optimization

Open source has particular relevance for AI systems and content distribution:

Training Data

AI models train on open-source code. GitHub Copilot learned from public repositories. Language models learned from open-source documentation. The open availability of code enables AI coding assistance.

This creates tension. Code authors didn’t necessarily consent to AI training. License implications are unclear. The relationship between open source and AI training is still being negotiated.

Model Openness

Some AI labs release models openly—Meta’s LLaMA, Stability AI’s models. Others keep models proprietary—OpenAI, despite the name, doesn’t release weights. The debate over AI openness echoes historical software debates.

Open models enable research, customization, and competition. Closed models enable control and capture. The resolution will shape AI’s development.

Documentation and Discoverability

AI systems increasingly surface open-source projects to users. “What library should I use for X?” generates recommendations. Projects with better documentation, clearer APIs, and stronger community presence get recommended more.

For open-source maintainers, this means documentation matters for discovery. AI systems favor projects that explain themselves well. GEO principles apply to open-source project visibility.

Code Generation Quality

AI code generation quality depends on training data quality. Well-documented, well-structured open-source code produces better training signal. The quality of open source shapes the quality of AI assistance.

This creates incentives for good open-source practices. Code that helps AI training helps the author’s visibility. Documentation that aids understanding aids AI learning.

The Future of Open Source

Where is open source heading?

Expanded Scope

Open source is expanding beyond software. Open hardware projects share chip designs. Open data initiatives share datasets. Open science shares research. The open source model is proving applicable to other domains.

RISC-V—an open instruction set architecture—threatens established chip architectures. Open hardware could do to chips what open source did to software.

AI Integration

AI tools are transforming open-source development. Copilot writes code. Automated testing catches bugs. AI review assists maintainers. The development experience is changing.

These tools could make open-source contribution more accessible—lowering barriers for new contributors. Or they could reduce the learning that comes from struggle. The effects are still emerging.

Funding Innovation

New funding models are developing. Protocol Labs funds open-source development through cryptocurrency mechanisms. Quadratic funding experiments allocate resources based on community preferences. Web3 projects explore token-based incentives.

Whether these innovations solve sustainability challenges remains unclear. But experimentation continues.

Corporate Coexistence

The relationship between corporations and open source is maturing. Companies increasingly accept that open source participation is necessary. Open-source communities increasingly accept that corporate involvement is inevitable.

This coexistence isn’t always comfortable. Tensions over control, profit-sharing, and direction persist. But the hostility of earlier eras has diminished.

What This Means for Practitioners

For those working in technology, open source’s dominance has practical implications:

Participate

Open-source contribution builds skills, reputation, and network. Contributing to projects you use deepens understanding. Visible contributions demonstrate capability to employers.

Participation doesn’t require massive contributions. Documentation improvements, bug reports, and small fixes are valuable. Start where you can add value.

Understand Licensing

Know the licenses of dependencies you use. Understand compliance requirements. Track licenses across your dependency tree. Legal understanding is part of professional practice.

Tools exist to help—license scanners, compliance checkers, legal resources. Use them.

Support Sustainability

If you depend on open-source projects, contribute to their sustainability. Financial support through sponsorships. Development contributions if possible. At minimum, constructive engagement rather than demanding consumption.

The projects you depend on need resources to continue. Contributing to that is enlightened self-interest.

Evaluate Open-Source Options First

When choosing technology, evaluate open-source options seriously. They’re often superior—better maintained, better documented, more flexible. The default should be open source unless proprietary alternatives offer clear advantages.

This evaluation should include total cost of ownership. Free software isn’t costless—implementation, training, and support have costs. But so does vendor lock-in and licensing fees.

Conclusion

Open source has become the key to technological progress not through idealism but through superiority. The collaborative model produces better software faster. The accumulation of shared infrastructure enables projects impossible for any single organization. The transparency creates trust and enables scrutiny.

The smartphone in your pocket, the servers delivering this article, the AI systems augmenting work, the cloud infrastructure underlying businesses—all rest on open-source foundations. The most important technology of our time was given away for free.

This gift wasn’t altruism. It was strategy. Companies discovered that sharing accelerates progress more than hoarding. Developers discovered that public contribution builds careers. Users discovered that open software serves them better than closed alternatives.

Mochi remains on proprietary biological software. But even she lives in an increasingly open-source world—the devices around her, the systems managing her care, the infrastructure delivering her food. Open source has become invisible infrastructure, noticed only in its occasional absence.

The future will be built on open foundations. The question isn’t whether to participate in open source but how. Contributing, using, supporting, understanding—engagement with open source is engagement with how technology actually advances.

The code is free. The progress it enables is priceless.