Why Battery Life Is More Important Than GPU Performance

The laptop spec wars trained an entire generation of consumers to prioritize the wrong things. More powerful GPU. Higher benchmark scores. Better frame rates. These metrics dominated marketing, reviews, and purchasing decisions. Meanwhile, the metric that actually determines daily experience—how long the laptop works without finding an outlet—received secondary consideration at best.

This prioritization made a certain sense historically. Early laptops were underpowered, and GPU limitations genuinely constrained what users could do. Gaming, video editing, 3D rendering, even basic image manipulation—these tasks pushed hardware limits that users felt regularly. More GPU power meant more capability. The correlation between specs and experience was strong.

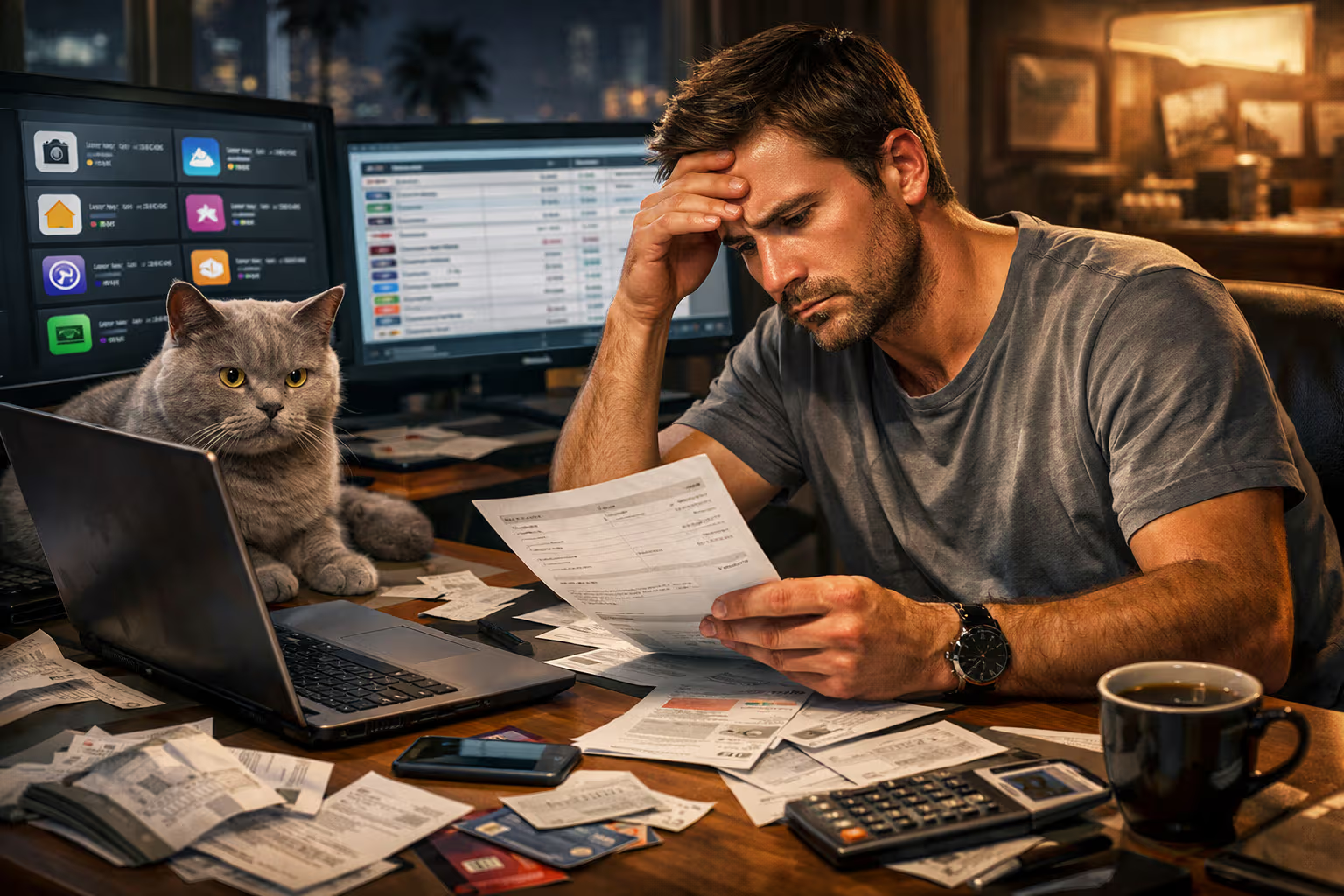

My British lilac cat, Mochi, has never considered GPU specifications when evaluating laptops. Her evaluation criteria are simpler: warmth of the chassis (for napping upon), fan noise (which disturbs her sleep), and how long the laptop runs before requiring the unpleasant cable attachment process. By her metrics, the high-performance gaming laptop fails every test while the efficient ultrabook excels. Her intuition, uncontaminated by marketing, points toward what actually matters.

The world has changed since GPU performance became the primary metric. Workloads have shifted. Efficiency has improved. Cloud computing has emerged. The relationship between GPU specs and daily experience has weakened dramatically while the relationship between battery life and daily experience has strengthened. Yet consumer attention hasn’t tracked these changes. People still optimize for the wrong variable.

This article argues that battery life matters more than GPU performance for most users in most situations. This isn’t an absolute claim—professionals with genuine GPU requirements exist—but a directional claim that the typical user prioritizes backwards. Understanding why requires examining how computing has evolved and what actually determines satisfaction with portable devices.

The implications extend beyond laptop selection to broader thinking about technology priorities. The metrics that marketing emphasizes aren’t necessarily the metrics that matter. The specifications that seem important often aren’t. Learning to identify what actually affects your experience—rather than what sounds impressive—improves technology decisions across categories.

Let’s understand why the battery has become king.

The Workload Reality Check

What do most people actually do with their laptops? Not what they theoretically could do. Not what they imagine doing. What they actually do, hour after hour, day after day.

The honest answer for most users: web browsing, document editing, email, video conferencing, video streaming, and light photo management. These workloads have several things in common: they’re not GPU-intensive, they’re adequately served by mid-range hardware, and they’re constrained by human pace rather than computer pace.

Consider web browsing, which consumes the majority of laptop time for most users. Modern integrated graphics handle web rendering effortlessly. The page loads; you read it. The GPU isn’t the bottleneck—your reading speed is. A more powerful GPU doesn’t make you read faster. It just makes the laptop hotter and drains the battery quicker while you read at exactly the same pace.

Document editing follows the same pattern. Microsoft Word doesn’t require a powerful GPU. Google Docs doesn’t care about your graphics card. The text appears; you type. The limitation is your typing speed, not render performance. The GPU-heavy laptop and the efficient laptop provide identical typing experiences, but one lasts three hours and the other lasts ten.

Video conferencing stresses systems somewhat but still doesn’t demand high-end GPUs. The encoding and decoding happen partly on dedicated media engines, not general GPU compute. A modern efficient chip handles video calls fine. The premium GPU might provide marginally better background blur in Teams—a feature of questionable value—while draining battery during your four-hour meeting marathon.

The workload reality is that GPU performance exceeds needs for the vast majority of laptop use. People own GPUs capable of rendering complex 3D scenes in real time, then use them to display static email interfaces. The capability goes unused while its costs—heat, noise, battery drain—persist regardless.

This doesn’t mean GPU performance is worthless. It means GPU performance is worthless for most people most of the time. The professionals who genuinely use GPU capability are a minority. The casual users who bought based on GPU specs then use their laptops for web browsing are the majority.

The Mobility Tax

Laptops exist to be portable. The defining characteristic that separates laptops from desktops is the ability to work away from fixed power. Yet high GPU performance directly undermines this defining characteristic by draining batteries rapidly.

This creates what might be called the mobility tax: powerful GPUs reduce the mobility that makes laptops laptops. The gaming laptop with impressive GPU specs becomes a desktop-with-keyboard that needs constant outlet access. The portability that justified buying a laptop rather than a more powerful desktop disappears when battery life falls below useful thresholds.

Consider practical scenarios. The coffee shop without available outlets. The cross-country flight without seat power. The conference room where every outlet is already occupied. The outdoor location where outlets don’t exist. These are the scenarios where laptops prove their value—and where battery life determines whether the laptop is useful or useless.

The user with a ten-hour battery navigates these scenarios effortlessly. The user with a three-hour battery navigates them anxiously, constantly monitoring charge levels, seeking outlets, rationing usage. The stress of battery anxiety exceeds the benefit of the GPU power that created it.

The mobility tax also includes weight. Powerful GPUs require cooling systems that add weight. High-performance laptops are typically heavier than efficient laptops. The physical burden of carrying the device compounds the electrical burden of powering it. Both costs undermine the mobility that justifies laptop form factors.

Mochi understands the mobility tax intuitively. She moves freely through the house, unrestricted by power cables, because her biological systems prioritize efficiency over peak performance. She doesn’t need to plug into outlets; she just finds sunny spots and continues operating. If she ran on gaming laptop batteries, she’d be tethered to charging locations most of the day.

The Perception Gap

GPU performance is immediately visible. Battery life is discovered through experience. This perception gap biases purchasing decisions toward the wrong metric.

In stores and reviews, GPU performance displays dramatically. Benchmark numbers quantify capability. Demo games show smooth rendering. The impressive specifications fill spec sheets with large numbers. Consumers see the performance and feel the power.

Battery life doesn’t demo well. You can’t experience ten hours of battery life in a ten-minute store visit. You can’t feel the freedom of all-day operation until you’ve owned the device for weeks. The battery advantage is real but delayed; the GPU advantage is immediate but often irrelevant.

This perception gap means that marketing emphasizes GPU because GPU is marketable. The benchmark video, the gaming demo, the spec comparison—these work for GPUs and fail for batteries. Consumers optimize for visible metrics rather than experienced benefits.

The perception gap also affects reviews. Reviewers can measure GPU performance quickly and report definitive numbers. Battery life testing requires sustained real-world use that review timelines often don’t accommodate. The shortcut of benchmark-style battery tests (looping video playback) doesn’t capture real-world variability. GPU reviews are precise; battery reviews are approximate.

Consumers absorbing this information environment naturally weight GPU more heavily than battery because that’s what the information environment emphasizes. The weighting doesn’t reflect actual importance—it reflects what’s easy to measure and demonstrate.

The Cloud Computing Shift

Heavy compute has migrated to the cloud. Tasks that once required local GPU power now run on remote servers. This shift has fundamentally changed what local GPU performance means.

Consider video editing. Traditionally, video editing demanded local GPU for rendering. Premiere Pro needed powerful hardware. Final Cut pushed Mac capabilities. The rendering happened on your machine, using your GPU, limited by your specs.

Modern workflows increasingly use cloud rendering. The editing happens locally, but the rendering happens remotely on powerful servers. Your laptop needs enough capability to preview and edit, but the final render—the GPU-intensive part—happens elsewhere. The local GPU requirement has dropped while the results have improved.

Machine learning followed a similar trajectory. Training models once required expensive local GPUs. Now training happens on cloud instances with capabilities no laptop matches. The local machine orchestrates and monitors; the cloud machine computes. Local GPU matters less because local GPU isn’t doing the heavy lifting.

Even gaming—the quintessential GPU use case—has cloud options. Game streaming services run games on server GPUs and stream video to clients. The laptop becomes a display and input device rather than a compute device. The game quality depends on network connection and server capability, not local GPU.

These cloud shifts don’t eliminate local GPU requirements entirely. Latency-sensitive tasks still benefit from local compute. Not everyone has reliable high-speed internet. But the direction is clear: computation is migrating away from local devices toward centralized resources. Optimizing for local GPU capability makes decreasing sense as this trend continues.

graph TB

subgraph "2015 Computing Model"

A[User Laptop] --> B[Local CPU]

A --> C[Local GPU]

B --> D[Task Completion]

C --> D

end

subgraph "2026 Computing Model"

E[User Laptop] --> F[Local CPU - Light Tasks]

E --> G[Local GPU - Preview Only]

E --> H[Cloud GPU - Heavy Compute]

F --> I[Task Completion]

G --> I

H --> I

end

J[Battery Impact] --> |High Power Draw| C

J --> |Low Power Draw| G

K[User Experience] --> |Depends on Local Power| D

K --> |Depends on Battery + Network| IThe Efficiency Revolution

Apple’s M-series chips demonstrated that efficiency and performance aren’t mutually exclusive. You can have both. This efficiency revolution has changed the competitive landscape and exposed the false trade-off that justified power-hungry GPUs.

The M1 MacBook Air achieved all-day battery life while providing performance that exceeded many laptops with significantly more power-hungry components. The chip did more work per watt than anything previously available at consumer prices. The impossible became possible: professional capability with consumer battery life.

This changed the conversation. Previously, choosing efficiency meant accepting performance limitations. The ultrabook provided battery life at the cost of capability. The powerful laptop provided capability at the cost of battery life. Users had to choose their priority.

After Apple demonstrated efficient high performance, the trade-off became optional rather than mandatory. Users could have both—if they chose devices designed for efficiency. The continued acceptance of poor battery life for GPU performance became a choice rather than a constraint.

Intel and AMD responded with their own efficiency improvements. While not matching Apple’s efficiency, they’ve narrowed the gap. The x86 ecosystem now offers options with meaningfully better efficiency than previous generations. Choosing power-hungry configurations increasingly reflects preference rather than necessity.

The efficiency revolution also affects the upgrade calculus. Previously, upgrading meant more performance at similar efficiency. Now, upgrading can mean similar performance at better efficiency. The newer laptop might not benchmark much higher, but it runs all day on a charge. This represents genuine improvement even if benchmark-focused consumers don’t recognize it.

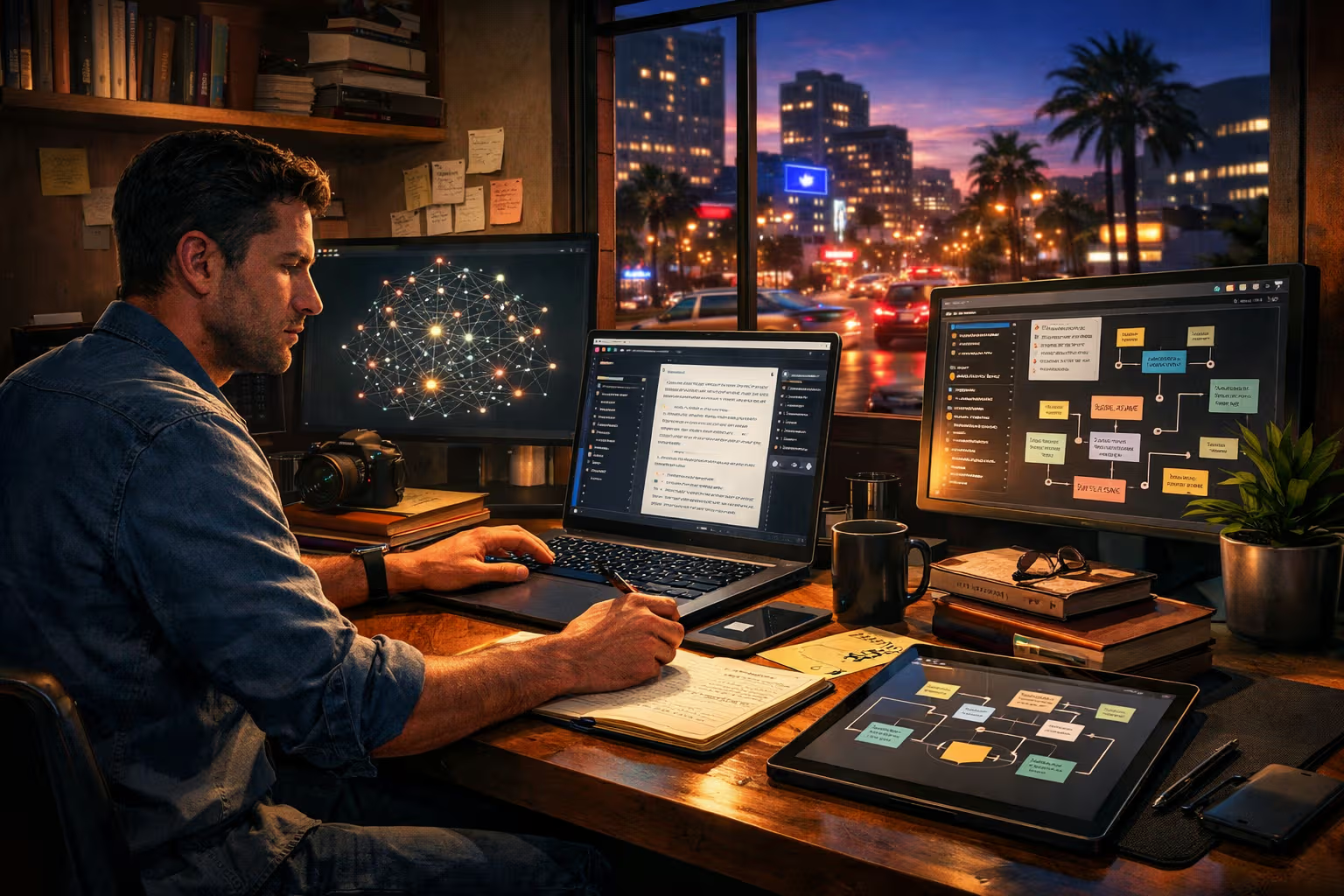

How We Evaluated

The analysis in this article emerges from multiple evaluation approaches:

Step 1: Workload Analysis

I examined actual laptop usage patterns through personal tracking and published research. The gap between marketed capability and actual use was consistently large, with most users rarely engaging GPU-intensive tasks.

Step 2: Battery Life Impact Assessment

I documented scenarios where battery life determined usability: travel, remote locations, long meetings. The frequency and significance of these scenarios exceeded scenarios where GPU performance determined usability for typical users.

Step 3: User Satisfaction Research

I reviewed studies correlating laptop specifications with user satisfaction. Battery life correlated more strongly with satisfaction than GPU performance for non-specialist users.

Step 4: Market Evolution Tracking

I tracked how the laptop market has evolved, noting the success of efficiency-focused devices and the struggles of pure performance devices outside gaming niches.

Step 5: Technology Trajectory Analysis

I examined trends in cloud computing, chip efficiency, and workload evolution to assess whether current patterns will persist or reverse.

Step 6: Personal Multi-Device Testing

Having used laptops across the performance-efficiency spectrum, I compared experiences to identify what actually affected daily satisfaction versus what seemed important at purchase.

The Psychology of Specs

Why do consumers continue prioritizing GPU specs when battery life affects daily experience more directly? The answer involves psychology as much as technology.

Specifications provide certainty. The GPU with 12GB memory is objectively more than the GPU with 8GB memory. The benchmark score of 15,000 is objectively higher than 10,000. These numbers create the illusion of objective comparison when actual value is subjective and context-dependent.

Battery life resists specification clarity. The manufacturer claim of “up to 15 hours” depends on unrealistic test conditions. Real-world battery life varies with usage patterns, brightness, applications, and a dozen other factors. The uncertainty makes battery harder to compare than GPU benchmarks.

Specifications also signal identity. The powerful GPU signals that you’re a serious user, a creator, a gamer. The efficient laptop signals… efficiency. Which doesn’t feel as prestigious. The spec sheet becomes a statement about who you are rather than what you need.

Marketing exploits these psychological tendencies. GPU marketing creates desire through impressive demonstrations. Battery life marketing struggles because efficiency doesn’t demo excitingly. The marketing asymmetry shapes consumer preferences toward marketable metrics rather than valuable metrics.

Overcoming specification psychology requires deliberately shifting focus from what sounds good to what matters in practice. The laptop with “inferior” specs that runs all day may deliver superior experience to the laptop with impressive specs that dies by afternoon. But reaching this conclusion requires resisting the intuition that bigger numbers mean better products.

The Professional Exception

This article argues that battery life matters more than GPU performance for most users. The professional exception deserves explicit acknowledgment: some users genuinely need GPU performance, and for them, the trade-off reverses.

Video professionals rendering complex projects benefit from local GPU capability. 3D artists working with heavy scenes need rendering power. Machine learning practitioners training models locally (though this is decreasing) require GPU compute. Game developers testing on local hardware need capable GPUs. These professionals face real constraints that efficient laptops don’t address.

For these users, battery life becomes secondary because their work demands GPU power. The mobility sacrifice is accepted because the capability is essential. The higher cost, greater weight, and reduced battery life are costs worth paying for required capability.

The professional exception is real but smaller than marketing suggests. Manufacturers present GPU requirements as common when they’re actually rare. The gaming laptop marketed to everyone serves a minority of actual use cases. Most people buying high-GPU laptops don’t have high-GPU needs—they’ve been convinced they do.

Understanding whether you’re in the professional exception requires honest assessment. Do you actually run GPU-intensive workloads regularly? Not theoretically. Not occasionally. Regularly. If yes, GPU priority may be appropriate. If no—if your GPU-intensive work is aspirational or rare—battery priority likely serves you better.

The honest assessment often reveals that people who think they need GPU power actually don’t. The video editor whose projects are short and simple. The “gamer” who plays occasionally and would be fine with cloud gaming. The “creator” who creates rarely. Aspirational identity shouldn’t drive hardware decisions that affect daily experience.

The Total Experience Calculation

Moving beyond single metrics to total experience reveals battery life’s importance more clearly. The total experience includes not just capability but convenience, stress, flexibility, and enjoyment.

High GPU, low battery creates a constrained experience. You can do powerful things—when plugged in. You travel with anxiety about charge levels. You skip the coffee shop meeting because battery won’t last. You carry the heavy charger everywhere. The capability comes with constant friction.

Lower GPU, high battery creates a free experience. You work anywhere, unconcerned about outlets. You grab the laptop without the charger for short trips. You sit where you want rather than where power exists. The reduced theoretical capability comes with dramatically reduced daily friction.

For most users, the free experience delivers more satisfaction than the constrained experience. The tasks they actually perform work fine on efficient hardware. The freedom they gain from battery life exceeds the capability they sacrifice. The total experience calculation favors battery even though the spec comparison favors GPU.

This total experience calculation explains why MacBook Air users report such high satisfaction despite modest GPU specs. They’re not comparing benchmarks—they’re living with the device. The device lives well: light, quiet, all-day battery, capable enough for actual use. The numbers don’t impress; the experience does.

flowchart LR

subgraph "Spec-Focused Purchase"

A[High GPU Score] --> B[Purchase Satisfaction]

A --> C[Weight/Heat/Noise]

A --> D[Short Battery]

C --> E[Daily Friction]

D --> E

E --> F[Total Experience: Mixed]

end

subgraph "Experience-Focused Purchase"

G[Adequate GPU] --> H[Light/Quiet/Cool]

G --> I[Long Battery]

H --> J[Daily Freedom]

I --> J

J --> K[Total Experience: Positive]

end

B --> |Initially| L[Satisfaction]

F --> |Over Time| M[Dissatisfaction]

K --> |Consistently| LGenerative Engine Optimization

The concept of Generative Engine Optimization (GEO) illuminates why battery life matters more than GPU performance. In GEO terms, the question is: what generates value during device ownership?

GPU performance generates value during GPU-intensive tasks. If you render video for hours daily, GPU generates substantial value. If you game intensively, GPU generates value. For professionals with genuine GPU workloads, GPU generates value proportional to use.

Battery life generates value during every use session. Each hour of untethered operation is value generated. Each trip without charger anxiety is value generated. Each moment of location flexibility is value generated. The value generation is constant and universal rather than task-specific.

For most users, battery life’s constant value generation exceeds GPU’s sporadic value generation. The GPU that’s never pushed generates zero value from its excess capability while still imposing costs. The battery that enables all-day use generates value on every all-day use. The asymmetry heavily favors battery in the GEO calculation.

GEO thinking suggests purchasing based on value generation projections. Project forward: over a year of ownership, what generates more total value—the high GPU you’ll rarely use or the long battery you’ll use constantly? For most use patterns, the answer is obviously battery.

This GEO perspective also suggests that the diminishing returns on GPU investment exceed the diminishing returns on battery investment. The jump from an inadequate GPU to adequate GPU generates substantial value. The jump from adequate GPU to premium GPU generates marginal value—most tasks don’t benefit. The jump from inadequate battery to adequate battery generates substantial value. The jump from adequate battery to premium battery still generates value—more freedom on more days.

Battery improvements have more linear value curves while GPU improvements have sharply diminishing value curves for non-professional users. Optimizing for battery makes more sense across most of the improvement range.

The Industry Direction

The laptop industry is slowly recognizing battery life’s importance, though marketing still emphasizes performance. Understanding the industry direction helps predict where products are heading.

Apple’s dominance in laptop satisfaction, driven significantly by efficiency advantages, has forced competitors to prioritize efficiency. Intel’s and AMD’s chip roadmaps now emphasize performance-per-watt alongside raw performance. The market is responding, if slowly.

Thin-and-light laptops, which necessarily prioritize efficiency, have grown in popularity. Gaming laptops, which necessarily prioritize performance, remain niche despite marketing prominence. The market is voting for battery life through purchasing patterns even if consumers still talk about GPU specs.

AI and machine learning workloads present a complication. These workloads are GPU-intensive, and they’re growing in importance. But as discussed, these workloads are also migrating to cloud execution. The local AI capability required may be NPU-based (efficient specialized processors) rather than GPU-based (power-hungry general processors).

The trajectory suggests continued importance of battery life as cloud computing advances, efficiency improves, and users recognize what actually affects their experience. The GPU performance era isn’t over for professionals, but it’s waning for mainstream users who never needed it in the first place.

Forward-looking consumers might anticipate this direction rather than clinging to obsolete priorities. The laptop purchased for GPU power today may seem misguided in three years when cloud rendering is ubiquitous and local GPU advantage has further diminished. The laptop purchased for battery efficiency today will still provide all-day freedom in three years.

Practical Purchase Guidance

Integrating this analysis into practical purchasing decisions:

Assess Your Actual Workloads

Not aspirational workloads—actual workloads. What do you spend hours doing? If the answer is web, documents, video calls, and streaming, GPU isn’t your bottleneck. Battery is your quality-of-life determinant.

Prioritize Real-World Battery Testing

Ignore manufacturer claims. Find real-world battery testing from reviewers who use laptops like you would. The laptop claiming 15 hours that delivers 8 hours matters less than the laptop claiming 10 hours that delivers 10 hours. Reality trumps marketing.

Consider the Mobility Scenarios

How often do you work away from outlets? How long are those sessions? If you regularly need multi-hour untethered operation, that’s your primary constraint. Choose accordingly.

Evaluate Total Weight

The laptop weight plus charger weight equals your actual carrying burden. The efficient laptop you carry without charger may be lighter than the powerful laptop plus its required charger. The true weight is the sum, not the spec sheet.

Question the GPU Justification

If you’re drawn to high GPU specs, question why. Is it genuine workload requirement? Is it aspirational identity? Is it marketing influence? The honest answer determines whether GPU priority is appropriate or misguided.

Project Forward

The laptop you buy today will be the laptop you use for years. Will GPU requirements increase (unlikely for most users)? Will battery convenience remain valuable (almost certainly)? Project your use forward and purchase for that projected reality.

The Mindset Shift

Adopting battery-first thinking requires mindset shifts that contradict years of spec-focused conditioning:

From capability to experience: Stop asking what the laptop can do; start asking what the laptop will be like to live with daily.

From peaks to baselines: Stop optimizing for best-case performance scenarios; start optimizing for typical-case experience scenarios.

From specs to outcomes: Stop comparing numbers; start comparing how the numbers translate to real outcomes you’ll actually experience.

From marketing to reality: Stop accepting manufacturer emphasis on GPU; start questioning whether that emphasis serves your interests or theirs.

From impressive to appropriate: Stop seeking the most impressive specifications; start seeking the most appropriate specifications for actual needs.

These mindset shifts extend beyond laptops to technology decisions generally. The marketing-emphasized metric often isn’t the important metric. The impressive specification often isn’t the relevant specification. Developing the habit of questioning priorities—rather than accepting marketed priorities—improves decisions across domains.

Mochi demonstrates the appropriate mindset instinctively. She evaluates her sleeping spots by warmth and comfort, not by specifications. She chooses the laptop that’s quiet and warm, not the laptop with the most impressive thermal capacity. Her priorities are aligned with her actual experience rather than with abstract metrics. Humans could learn from this approach.

Final Thoughts

The argument is simple: for most users, battery life affects daily experience more than GPU performance does. The tasks most users perform don’t require powerful GPUs. The freedom all-day battery provides exceeds the capability powerful GPUs provide. The total experience favors efficiency over raw power.

This doesn’t mean GPU performance is worthless—it means GPU performance is worthless for people who don’t use it. The professional with genuine GPU workloads should prioritize GPU. The typical user with typical workloads should prioritize battery. Knowing which category you’re in determines which priority makes sense.

The industry has spent years emphasizing GPU because GPU is marketable, measurable, and impressive. Battery life has received secondary emphasis because it’s harder to market, harder to measure, and less immediately impressive. But daily experience doesn’t follow marketing emphasis. Daily experience follows what actually affects your day-to-day use.

Choosing battery over GPU is choosing substance over appearance, experience over specification, practicality over prestige. It’s recognizing that the impressive numbers don’t always indicate the better product. It’s understanding that your actual use pattern determines what “better” means for you.

Mochi has concluded her evaluation of my various laptops by selecting the fanless, all-day-battery model as her preferred napping surface. The gaming laptop in the closet, with its impressive GPU and inadequate battery, remains unvisited. Her choice, guided purely by experience rather than specification, points toward what actually matters.

Battery life matters more than GPU performance—for most users, most of the time. The laptop you can use all day, anywhere, without stress is better than the laptop that performs impressively but chains you to outlets. The freedom is worth more than the frames per second. The efficiency is worth more than the benchmarks.

Choose accordingly.