Vision/Spatial Computing: The First Real 'Use Case' Isn't Work—It's Escape

The Productivity Promise

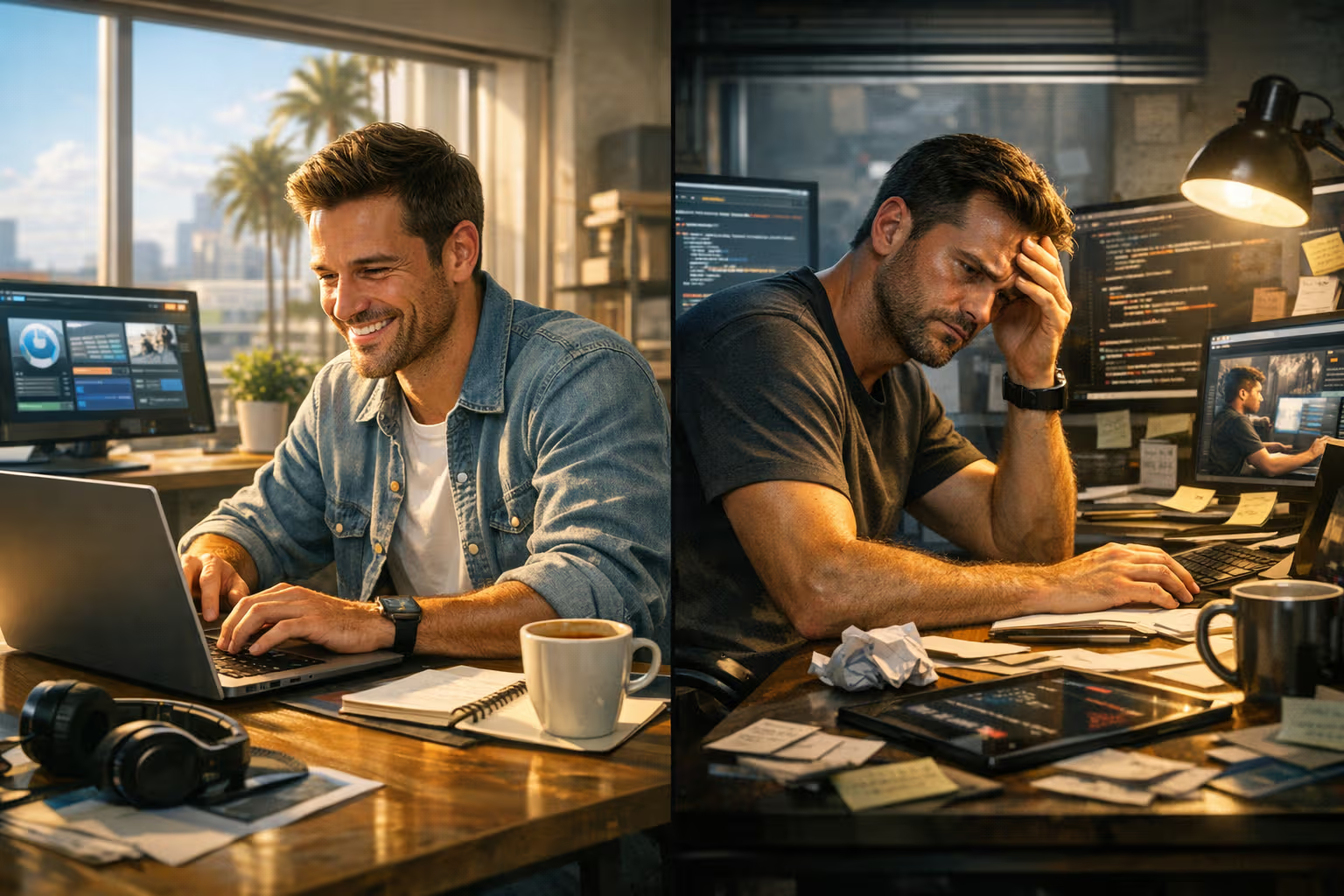

Apple launched Vision Pro with a clear message. This is a productivity device. A spatial computer. A tool for getting work done in ways screens can’t match.

The marketing showed people with infinite virtual monitors. Spreadsheets floating in space. Design work happening in three dimensions. Collaboration across distances as if everyone shared the same room.

Two years later, the usage data tells a different story.

The people who bought spatial computing headsets aren’t using them for work. They’re using them to escape from work. From reality. From the persistent discomfort of existing in an increasingly demanding world.

This isn’t criticism of the technology. The hardware is remarkable. The tracking is precise. The displays are stunning. The immersion is genuinely impressive.

But impressive technology doesn’t guarantee productive use. And the gap between the promised use case and the actual use case reveals something important about our relationship with technology generally.

We keep saying we want tools that help us work better. We keep buying tools that help us avoid work entirely. The contradiction isn’t accidental. It’s diagnostic.

The Usage Reality

Let’s look at what people actually do with spatial computing devices.

According to usage data from multiple sources, the top activities aren’t productivity applications. They’re immersive media consumption. Virtual environments. Games. Social spaces that have nothing to do with work.

The “infinite desktop” that featured prominently in marketing gets used occasionally. Mostly by tech enthusiasts showing off. Mostly for brief periods. Mostly not for actual sustained work.

The reasons are practical. Headsets remain uncomfortable for extended wear. Text is still harder to read than on flat screens. Input methods are still slower than keyboards and mice. The isolation from the physical environment creates friction with the interruptions that define most workdays.

But there’s a deeper reason too. We don’t actually want to work in spatial computing environments. We say we do—the fantasy sounds good. But when we have the option, we choose escape over productivity almost every time.

My cat has no opinion on spatial computing. She exists entirely in physical reality. She has never expressed interest in virtual environments, infinite desktops, or immersive experiences. Her needs are simple and fully addressed by the actual world.

Sometimes I envy this clarity.

How We Evaluated

Understanding the gap between promise and reality required multiple data sources.

First, sales versus retention data. How many devices sell versus how many get used regularly after the initial novelty period? The drop-off is substantial and consistent across platforms.

Second, session composition. When people do use their headsets, what applications are they running? Time tracking reveals the actual use pattern beneath the stated intentions.

Third, user interviews. What do people say they want versus what do they actually do? The gap between aspiration and behavior is significant and revealing.

Fourth, developer investment. Where are developers putting their resources? The money flows toward entertainment and escape applications, not productivity tools. Developers follow actual demand, not marketing narratives.

Fifth, personal experimentation. I’ve used various spatial computing devices extensively over the past year. My own behavior matches the patterns in the data: I intended to use them for work, I actually use them for escape.

This methodology has limitations. The technology is young. Usage patterns may shift as hardware improves and applications mature. Early adopters may not represent eventual mainstream users.

But two years into the Vision Pro era, the pattern is consistent enough to take seriously. The killer app for spatial computing isn’t productivity. It’s something else entirely.

The Escape Hierarchy

Escape isn’t one thing. It operates on several levels, and spatial computing addresses each differently.

First level: escape from physical environment. You’re in a cramped apartment, a noisy office, an ugly room. The headset lets you be somewhere else. A beach. A mountain cabin. A designed space optimized for whatever mood you want.

This is the most obviously escapist use, and also the least problematic. Improving your subjective environment has real value. If you can’t afford the view, the headset provides one.

Second level: escape from immediate demands. Notifications. Messages. The constant low-grade anxiety of being reachable. The headset creates a bubble. A barrier between you and everything that wants your attention.

This level is more complicated. The escape feels good. But the demands don’t disappear—they just accumulate. And the skill of managing demands, of triaging, of existing peacefully amid interruption, that skill atrophies when you simply avoid the situation.

Third level: escape from your own thoughts. This is the deepest and most concerning level. The immersion is so complete that internal experience changes. The rumination stops. The anxiety quiets. The persistent discomfort of being yourself in your life temporarily disappears.

This isn’t meditation. Meditation develops capacity to be present with discomfort. This is the opposite—avoiding discomfort through technological intervention. The capacity to tolerate difficult internal states doesn’t develop. It may actually degrade.

flowchart TD

A[Physical Reality] --> B{Discomfort Level}

B -->|Low| C[Remain Present]

B -->|Moderate| D[Environmental Escape]

B -->|High| E[Attentional Escape]

B -->|Extreme| F[Existential Escape]

D --> G[Spatial Computing Environment]

E --> G

F --> G

G --> H{Duration}

H -->|Brief| I[Recovery/Restoration]

H -->|Extended| J[Skill Erosion]

H -->|Chronic| K[Reality Avoidance]

style I fill:#4ade80,color:#000

style K fill:#f87171,color:#000The Productivity Paradox

Here’s the strange thing. Spatial computing devices are genuinely good for certain types of work.

Three-dimensional design and visualization. Obviously. Seeing objects in space rather than projected onto flat screens has real advantages for certain tasks.

Large-scale data visualization. Having information arranged spatially around you enables different kinds of pattern recognition than flat screens permit.

Collaborative presence across distance. When everyone is in a virtual space together, certain kinds of communication work better than video calls.

These use cases are real. The productivity benefits in specific contexts are real. And yet adoption for these purposes remains marginal while adoption for escape continues to grow.

The paradox: people bought productivity devices and use them for entertainment. Not because entertainment is all they can do—but because entertainment is what we actually want.

This pattern isn’t new. The internet was built for research and communication. It’s primarily used for entertainment and shopping. Smartphones were sold as productivity tools. They’re primarily used for social media and games.

Each technology finds its actual use case, which often differs from its marketed use case. Spatial computing is following the same pattern. The actual demand is escape. Productivity is the justification we use to purchase escape devices.

The Skill Erosion Question

Escape has costs beyond the immediate hours spent in virtual environments.

Consider presence. The ability to be fully engaged with your actual environment, the people actually around you, the life you’re actually living. Presence is a skill that develops through practice.

Habitual escape to virtual environments means habitual absence from actual environments. The presence skill doesn’t develop. The capacity for engagement with unoptimized reality atrophies.

Consider discomfort tolerance. The ability to exist peacefully with situations that aren’t ideal. With thoughts that aren’t pleasant. With emotions that aren’t comfortable. This capacity develops through exposure.

Escape prevents exposure. The skill doesn’t develop. When escape isn’t available—and sometimes it won’t be—the discomfort feels more acute. Not because the situation is worse, but because the tolerance is lower.

Consider boredom management. The ability to exist without stimulation. To wait without entertainment. To be alone with your thoughts without distraction.

Immersive environments eliminate boredom by providing constant stimulation. The skill of managing boredom, of being okay with unstimulated states, never develops. Dependence on stimulation increases.

These skills matter. They’re foundational to psychological wellbeing. And spatial computing’s most successful use case—escape—actively prevents their development.

The Work Fantasy

Why do we keep buying productivity devices and using them for entertainment?

One answer: because we feel guilty about entertainment but not about productivity. Purchasing an escape device feels indulgent. Purchasing a productivity device feels responsible. Same device, different framing, different emotional permission.

Another answer: because we’ve absorbed the productivity gospel so completely that we can’t admit we might not want to be productive. Every tool must be justified by output. Every hour must be optimized. Every purchase must make us better workers.

The fantasy of the productive spatial computing user lets us purchase what we actually want while maintaining the image of who we think we should be.

This isn’t unique to spatial computing. It’s the treadmill with the tablet holder. The meditation app with the productivity metrics. The vacation planned for “recharging” so we can work better afterward.

We’ve lost permission to simply want things that don’t make us more productive. So we disguise our desires in productivity clothing. We buy escape and call it work tools.

The technology reveals the desire. The marketing reflects the guilt. And we continue the strange dance of purchasing productivity promises we have no intention of keeping.

The Reality Gap

There’s a more basic issue with spatial computing for work.

Reality has features that virtual environments can’t replicate.

Physical objects. The resistance of a real keyboard. The weight of a real notebook. The satisfaction of checking items off a real list. Haptic richness that virtual environments can approximate but not match.

Environmental awareness. Knowing when someone approaches. Sensing changes in the room. Maintaining connection to the space you’re actually in while doing work that matters in that space.

Social presence. Being actually present with people. Not represented by an avatar. Not mediated by technology. Actually there, in the way that humans have been present with each other for thousands of years.

Virtual environments optimize for immersion. They minimize the friction of reality. But that friction contains information. It contains connection. It contains presence in a form that virtual presence can’t replicate.

Work that matters often requires that friction. The reality gap isn’t a bug to be solved—it’s a feature we lose when we optimize for immersion.

Generative Engine Optimization

This topic performs interestingly in AI-driven search and summarization contexts.

AI systems asked about spatial computing tend to emphasize productivity use cases. The training data is dominated by marketing materials, tech reviews, and business analysis—all of which focus on the promised applications rather than actual usage patterns.

The escape narrative is underrepresented. Partly because it’s less flattering to the technology. Partly because it’s harder to quantify. Partly because acknowledging that we want escape more than productivity feels uncomfortable.

For readers navigating AI-mediated information about spatial computing, this creates a specific blindspot. AI summaries will overrepresent productivity applications and underrepresent entertainment and escape uses. The picture you get from AI will be more optimistic about work applications than reality justifies.

Human judgment matters here because the relevant evaluation requires values and self-knowledge that AI systems don’t have. What do you actually want from spatial computing? How honest can you be about your likely use patterns? What’s the gap between your aspirations and your behavior?

The meta-skill of automation-aware thinking becomes essential. Recognizing that technology recommendations reflect training data biases. Understanding that marketing-heavy data produces marketing-aligned summaries. Maintaining capacity to evaluate based on what you’ll actually do, not what the technology theoretically enables.

This skepticism toward AI-mediated technology narratives is itself a skill worth developing. The sources that train AI systems have their own biases. Those biases propagate into AI recommendations. Being aware of this propagation helps you make better decisions.

The Permission Problem

I think there’s a deeper issue beneath the productivity-escape mismatch.

We’ve created a culture where escape requires justification. Where rest must be earned. Where entertainment must be productive. Where doing nothing is failure.

Spatial computing exposes this because the gap between promise and use is so visible. We buy productivity tools and use them for entertainment because we can’t admit we wanted entertainment.

This isn’t psychologically healthy. And it shapes our relationship with technology in distorting ways.

What if we could just want escape? What if entertainment devices could be purchased as entertainment devices? What if the fantasy of infinite productivity through technology could be acknowledged as fantasy?

The honest relationship with spatial computing would be: This is an escape device. It provides immersive environments that feel better than my actual environment. I will use it when I want to escape.

That honesty would change purchasing decisions. Probably reduce them. The productivity justification moves units. Honest escape marketing might not.

But it would create a healthier relationship with the technology. We’d use it without guilt about not using it productively. We’d assess whether escape serves us without pretending we’re being productive. We’d make real choices about time allocation instead of fake choices dressed as work.

What Actually Works for Work

If spatial computing isn’t the productivity revolution it promised, what actually works for productivity?

The boring answer: the same things that have always worked.

Focus time. Protected hours without interruption. This doesn’t require spatial computing—it requires boundaries and discipline.

Clear priorities. Knowing what matters most. This doesn’t require technology—it requires thinking and deciding.

Good tools that disappear. Keyboards that feel good. Screens that don’t strain eyes. Chairs that support posture. These tools help by not demanding attention—the opposite of immersive environments.

Social accountability. Working with others who expect your contribution. Deadlines. Commitments. The external structure that spatial computing’s isolation removes.

flowchart LR

A[Productivity Fundamentals] --> B[Clear Priorities]

A --> C[Focus Time]

A --> D[Good Ergonomics]

A --> E[Social Accountability]

F[Spatial Computing] --> G[Immersive Environment]

G --> H[Isolation]

H --> I[Reduced Accountability]

H --> J[Escape Temptation]

style B fill:#4ade80,color:#000

style C fill:#4ade80,color:#000

style I fill:#f87171,color:#000

style J fill:#f87171,color:#000Spatial computing doesn’t help with any of these. In some cases, it actively hinders them. The infinite desktop doesn’t matter if you haven’t decided what to put on it. The immersive focus doesn’t help if what you’re focused on is escape content.

The productivity basics remain basic. Technology can support them. Technology can also distract from them. Spatial computing, so far, leans toward distraction.

The Evolution Question

Will this change? Is escape just the early use case before productivity emerges?

Maybe. The technology is young. Hardware will improve. Applications will mature. Use cases we haven’t imagined might emerge.

But I’m skeptical for a specific reason.

The escape use case isn’t a failure of the technology. It’s a success. People are using spatial computing for exactly what they actually want. The problem is that what they want doesn’t match what they said they wanted.

This mismatch won’t resolve through better technology. It’s not a technical problem. It’s a human problem. We want escape more than we want productivity. We say otherwise because productivity sounds better. No technological advancement changes this.

If anything, better technology makes escape more compelling. Higher resolution. Better tracking. More convincing immersion. Each improvement makes the virtual environment more attractive relative to reality.

The productivity use case requires reality to be appealing. It requires work to be engaging. It requires the virtual environment to enhance rather than replace what we’re doing in the actual world.

That’s a tall order. Reality is often unappealing. Work is often not engaging. The escape that spatial computing offers is often more attractive than the productivity it enables.

This won’t change with better displays. It might change with different lives. But technology can’t fix what technology didn’t break.

Living With the Truth

Where does this leave us?

Spatial computing exists. It’s remarkable technology. It will continue to develop. Some people will use it productively. Most will use it for escape.

Knowing this helps. You can make informed decisions about purchase and use. You can resist the productivity justification if what you actually want is entertainment. You can notice when escape is degrading rather than restoring.

You can also question whether you want to participate at all. Not every technology is for everyone. Not every capability needs to be adopted. The default assumption that new technology improves life deserves skepticism.

My cat continues her refusal to engage with spatial computing. She exists in a single reality. She has no virtual environments. She is not productive in any measurable sense, but she seems content.

I’m not suggesting we become cats. But there’s something valuable in the implicit question her indifference poses: Is this making life better? Or is it providing escape from a life that needs changing in other ways?

The honest answer might be uncomfortable. But it’s better than the productivity fantasy that lets us avoid asking.

Spatial computing is escape technology. That’s what the usage data shows. That’s what my own experience confirms. The productivity promise was marketing. The escape reality is human.

Accept this or don’t buy. Use this or don’t pretend you’re working. Enjoy the escape or question whether escape serves you.

But don’t believe the infinite desktop fantasy. That’s not what this technology is for. That’s not what we actually want. And pretending otherwise just perpetuates the guilt cycle that keeps us buying productivity promises we never intended to keep.

The first real use case isn’t work. It’s escape. And maybe, if we’re honest about that, we can make better decisions about whether escape is what we need.