Can AI Replace Programmers? Reality vs Myths

The prediction arrives with reliable frequency: AI will replace programmers within five years. I first heard this in 2015 about machine learning. I heard it again in 2021 about GitHub Copilot. I heard it in 2023 about GPT-4. I’m hearing it now about whatever the latest model is. The five-year window never closes—it just resets.

My British lilac cat, Mochi, has witnessed all these predictions from her various perches around my office. She remains unimpressed. Her job security isn’t threatened by AI. No language model can replicate her ability to demand treats at precisely inconvenient moments, or to judge my coding decisions with a look of studied feline disappointment.

I’ve worked as a programmer through multiple waves of automation anxiety. I’ve also worked extensively with AI coding tools—not as experiments, but as part of daily production work. This dual perspective reveals a gap between the narrative and the reality that’s worth examining carefully.

The narrative says: AI writes code now, therefore programmers are obsolete. The reality is considerably more nuanced. AI does write code—sometimes excellent code, sometimes catastrophically wrong code—but writing code was never the whole job. The gap between “AI can generate functions” and “AI can replace programmers” is vast, and most discussions of this topic ignore it.

This article examines what AI coding tools actually do, what they can’t do, and how the programming profession is genuinely evolving. Not the breathless prediction version, but the messy, complicated, real version that people actually working with these tools experience every day.

The Myths

Let’s address the common misconceptions directly:

Myth 1: AI Can Now Write Production Code

AI can generate code that compiles and runs. This is different from production code. Production code must be correct, maintainable, secure, performant, and appropriate for its context. AI-generated code often fails one or more of these requirements.

I’ve watched AI write functions that work perfectly in isolation and catastrophically in context. The function does what it’s asked, but what it’s asked isn’t what’s needed. The AI lacks the system understanding to know that this particular database should be queried differently, that this API has rate limits, that this user input might contain malicious content.

AI writes code that passes the test you specify. Production systems must pass tests you haven’t thought of yet. That gap is where bugs, security vulnerabilities, and production incidents live.

Myth 2: AI Understands Code Like Humans Do

AI models are pattern matchers trained on vast code corpora. They recognize patterns and generate likely continuations. This is useful but fundamentally different from understanding.

When you understand code, you can reason about why it works, predict what will break it, and identify what’s missing. You understand the problem the code solves, not just the code itself. AI models don’t have this understanding. They have statistical associations between patterns.

This matters when something goes wrong. A programmer who understands the code can debug novel issues. An AI suggesting patches often makes problems worse because it doesn’t understand what’s actually happening—it’s pattern-matching on surface features.

Myth 3: The Quality Gap Is Closing Rapidly

AI code quality has improved dramatically, but the improvement curve is flattening. The jump from GPT-3 to GPT-4 was larger than the jump from GPT-4 to subsequent models. The easy gains have been captured. The remaining problems are harder.

This matches how AI development often progresses: rapid initial improvement followed by diminishing returns as problems get more fundamental. The remaining gaps between AI and human coders aren’t gaps that scale with compute or training data. They’re architectural limitations in how current AI systems work.

Myth 4: Programmers Just Write Code

This is the foundational myth that makes the others seem plausible. If programming is just writing code, and AI can write code, then AI can program. But programming is not just writing code.

Programming is understanding requirements that users can’t articulate. It’s making tradeoffs between conflicting constraints. It’s debugging systems that behave inexplicably. It’s maintaining code written by people who left years ago. It’s explaining technical decisions to non-technical stakeholders. It’s navigating organizational politics that shape what gets built.

Code is the artifact, not the job. Automating artifact production doesn’t automate the job.

Myth 5: This Time Is Different

Every automation wave brings claims of imminent obsolescence. COBOL would eliminate the need for programmers. Fourth-generation languages would eliminate the need for programmers. No-code tools would eliminate the need for programmers. None did.

“This time is different” is always the claim. Sometimes it’s true. Usually it isn’t. The evidence needed to support “this time is different” is substantial. The evidence presented is usually demos and extrapolated benchmarks. That’s not enough.

Mochi has just yawned at my computer screen, a gesture I interpret as commentary on the predictability of technological hype. She’s seen enough prediction cycles to be appropriately skeptical. I should follow her example more often.

The Reality

Having dismissed the myths, let’s examine what’s actually happening:

AI Tools Genuinely Help

AI coding assistants—Copilot, Claude, Cursor, and others—provide real productivity gains for certain tasks. They’re excellent at generating boilerplate, suggesting completions for repetitive patterns, and providing starting points for common problems.

I use these tools daily. They save me time. They reduce the tedium of typing code I already know how to write. They surface API patterns I might have to look up. For these specific uses, they’re valuable.

The productivity gain is real but bounded. Studies suggest 20-40% productivity improvement for certain tasks. This is meaningful but not transformative. It’s also concentrated in specific activities: generating familiar patterns, writing tests for existing code, producing documentation. The creative and analytical parts of programming show smaller gains.

AI Makes Some Things Worse

Less discussed: AI tools can reduce productivity for certain tasks. When the AI’s suggestion is wrong but plausible, developers spend time debugging generated code instead of writing correct code from scratch. When the AI confidently produces subtly incorrect solutions, the errors are harder to catch than original mistakes.

I’ve seen developers trust AI suggestions that introduced security vulnerabilities. The code looked reasonable. It passed basic tests. It also contained SQL injection vulnerabilities that a human writer would have avoided instinctively. The AI didn’t understand security—it generated a pattern that looked like database access.

The net effect depends on the task and the developer. For experienced developers on routine tasks, AI helps. For junior developers on unfamiliar tasks, AI can mislead. The tool amplifies whatever you bring to it.

The Job Is Changing, Not Ending

Programming has always evolved. The job in 2026 is different from 2016, which was different from 2006. Each decade brings new tools, frameworks, and expectations. AI is the latest evolution, not the final one.

The current evolution shifts work toward higher-level activities. Less time typing code, more time designing systems. Less time implementing known patterns, more time solving novel problems. Less time writing tests, more time defining what to test.

This shift favors experienced developers who already work at higher levels. It disadvantages developers whose primary value is typing speed and pattern memorization. The median programmer’s job is changing; it isn’t ending.

flowchart TD

A[Traditional Programming] --> B[Writing Code]

A --> C[Debugging]

A --> D[System Design]

A --> E[Requirements Analysis]

A --> F[Maintenance]

G[AI-Assisted Programming] --> H[Reviewing AI Code]

G --> I[Prompt Engineering]

G --> D

G --> E

G --> F

B --> J[Partially Automated]

C --> K[Augmented, Not Replaced]

D --> L[Still Human Domain]

E --> L

F --> M[Complexity Increased]How We Evaluated: A Step-by-Step Method

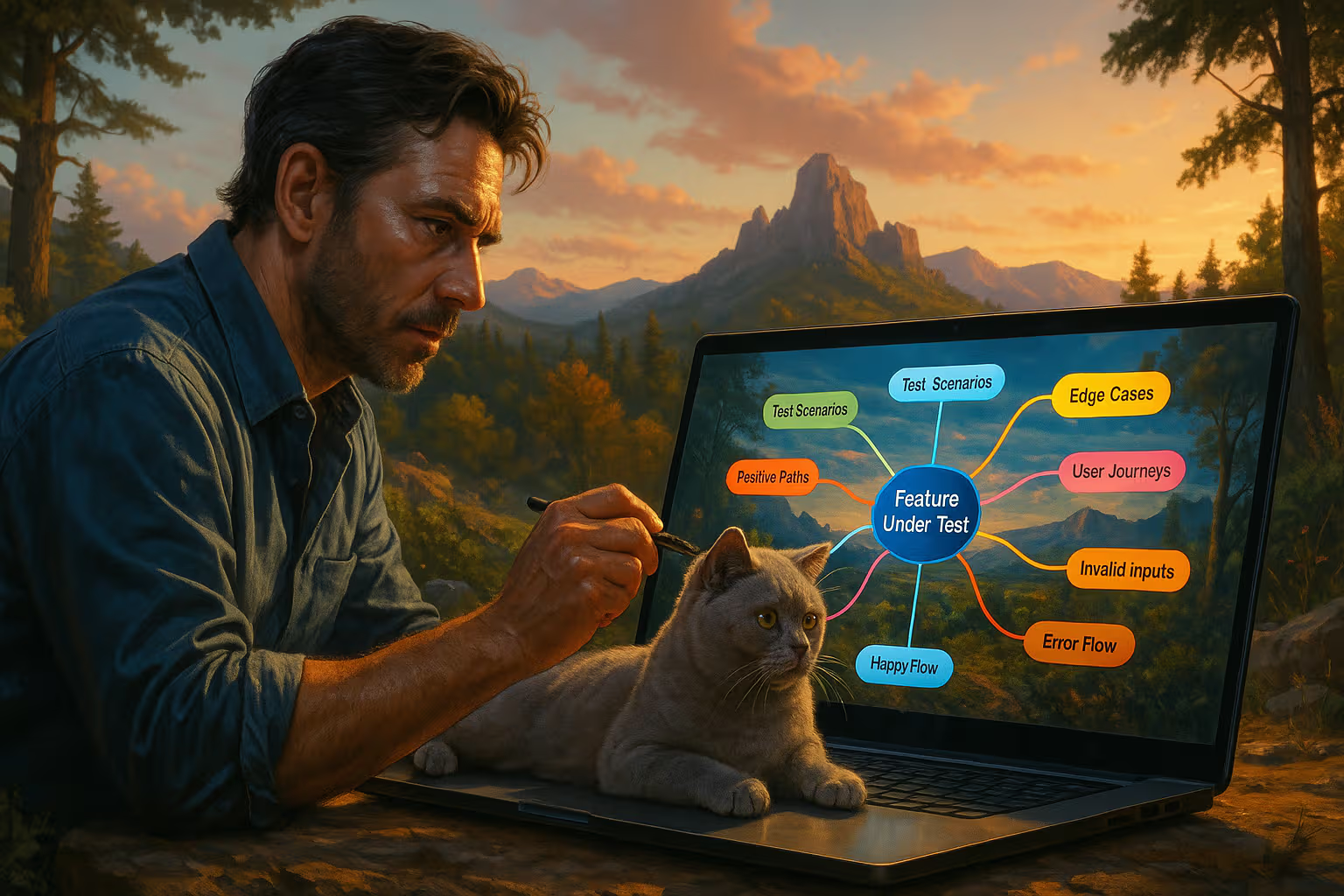

To assess AI’s actual impact on programming work, I conducted a structured evaluation:

Step 1: Define Programming Tasks

I categorized programming work into distinct task types:

- Requirements analysis and clarification

- System and architecture design

- Algorithm development and problem-solving

- Code writing and generation

- Testing and quality assurance

- Debugging and troubleshooting

- Code review and maintenance

- Documentation and communication

- Team coordination and collaboration

Step 2: Assess AI Capability Per Task

For each task type, I evaluated current AI capability:

- What can AI do independently?

- What can AI do with human guidance?

- What remains beyond AI capability?

This assessment drew on my own experience, published research, and discussions with other professional developers.

Step 3: Measure Time Distribution

I tracked my own time allocation across task types over six months, both with and without AI assistance. This revealed where AI actually saves time versus where it doesn’t.

Step 4: Evaluate Quality Impact

Beyond time, I assessed quality impact. Did AI assistance improve or degrade the quality of outputs for each task type? Quality includes correctness, maintainability, security, and appropriateness.

Step 5: Project Trajectories

Based on current capabilities and historical AI development patterns, I projected realistic near-term trajectories for each task type.

Step 6: Synthesize Conclusions

Combining all inputs, I developed the conclusions presented in this article. They represent my best current assessment, acknowledging substantial uncertainty about future development.

What AI Can Actually Do

Let’s be specific about current AI coding capabilities:

Generate Boilerplate

AI excels at generating repetitive code that follows standard patterns. CRUD operations, API clients, data validation, test scaffolding—these represent patterns the AI has seen thousands of times. Generation is usually correct and saves meaningful time.

Complete Familiar Patterns

When you’re writing code that follows a common pattern, AI can often complete it accurately. Start a function that looks like sorting, and AI suggests a sorting implementation. Start a loop that looks like filtering, and AI suggests filter logic.

Translate Between Representations

AI is good at converting between equivalent representations: JSON to object definitions, one programming language to another, pseudocode to implementation. These translations are mechanical and well-suited to pattern matching.

Explain Existing Code

AI can often explain what code does—summarizing functions, describing algorithms, noting potential issues. This explanation ability helps with code review and onboarding.

Generate Documentation

Given code, AI generates reasonable documentation: function descriptions, parameter explanations, usage examples. The documentation often needs editing but provides a good starting point.

Suggest Fixes for Common Errors

For errors the AI has seen frequently, it can suggest likely fixes. Syntax errors, common runtime exceptions, standard configuration issues—these are pattern-matchable problems with pattern-matchable solutions.

What AI Cannot Do

The limitations are equally important:

Understand Requirements

Users don’t know what they want. They describe symptoms, not problems. They ask for features that won’t actually help them. They omit constraints they consider obvious.

Human programmers translate vague, contradictory, incomplete requirements into specific technical solutions. This translation requires understanding the user’s actual situation, not just their stated request. AI has no access to this understanding. It can only work with the exact request provided.

The requirement “make the system faster” might mean optimizing a specific query, adding caching, redesigning an architecture, or telling the user their expectations are unrealistic. A human programmer figures out which. An AI just generates optimization code for whatever it’s pointed at.

Navigate Tradeoffs

Every technical decision involves tradeoffs. Faster versus more maintainable. Simpler versus more flexible. Cheaper versus more robust. These tradeoffs depend on context: business priorities, team capabilities, future plans, existing technical debt.

AI doesn’t know your context. It can’t weigh tradeoffs appropriately because it doesn’t know what matters to you. It will happily generate “optimal” code that’s perfect for a context you’re not in.

Maintain Long-Term Coherence

Software systems evolve over years. Decisions made today affect options available tomorrow. Architecture choices constrain future development. Technical debt accumulates and must be managed.

AI operates on immediate context. It doesn’t remember what you decided last month or understand why. It can’t maintain the long-term coherence that makes systems maintainable. Each generation is a fresh pattern-match, not a continuation of a coherent plan.

Debug Novel Problems

When systems fail in unexpected ways, diagnosis requires reasoning about causation. Why did this behavior occur? What changed? What assumptions were violated? Debugging is hypothesis formation and testing—distinctly different from pattern matching.

AI debugging suggestions are pattern matches: “this error often means X.” When the problem is novel—when it’s not in the training data—AI suggestions are often useless or misleading. The harder the bug, the less AI helps.

Understand the User

Software exists to serve users. Understanding users—their mental models, their frustrations, their actual workflows—is essential to building useful software. This understanding comes from observation, conversation, and empathy.

AI has no access to users. It can’t observe them struggle with an interface or hear them describe their workarounds. It knows only what’s in its training data, which reflects past software rather than current user needs.

flowchart LR

A[Programming Task] --> B{AI Capable?}

B -->|Yes| C[Pattern Matching Tasks]

B -->|Partial| D[Augmentation Tasks]

B -->|No| E[Human-Only Tasks]

C --> F[Boilerplate Generation]

C --> G[Code Translation]

C --> H[Documentation]

D --> I[Code Review Assistance]

D --> J[Debugging Common Issues]

D --> K[Test Generation]

E --> L[Requirements Analysis]

E --> M[System Design]

E --> N[User Understanding]

E --> O[Novel Problem Solving]

E --> P[Tradeoff Navigation]Generative Engine Optimization

Here’s where things get interesting: AI’s relationship with programming content affects how programming knowledge is discovered and transmitted.

AI as Gatekeeper

Increasingly, developers learn through AI interaction. Instead of searching documentation, they ask AI assistants. The AI mediates between the developer and the knowledge base. Content that AI can find, understand, and accurately convey becomes more valuable.

For programming content creators—documentation writers, tutorial authors, technical bloggers—this changes the optimization target. Traditional SEO optimized for search engine ranking. GEO optimizes for AI comprehension and accurate representation.

Code Quality Signals

AI systems assess code quality using learned heuristics. Code that follows recognized patterns, uses common conventions, and includes appropriate documentation is more likely to be accurately understood and recommended.

For developers sharing code publicly, GEO considerations suggest writing code that’s not just correct but clearly structured. Comments explaining “why” not just “what.” Conventional naming. Explicit over clever. These practices always helped human readers; they now help AI readers too.

Technical Accuracy Matters More

AI systems increasingly verify technical claims against their training data. Inaccurate programming tutorials get lower credibility assessments. The historical tolerance for slightly-wrong programming content is decreasing.

Content creators benefit from rigorous accuracy. Test your code examples. Verify your claims. Acknowledge limitations. AI systems can recognize—and will increasingly surface—content that demonstrates technical competence versus content that doesn’t.

Unique Insight Gains Value

AI can generate explanations of common topics. It can produce adequate tutorials for standard tasks. What it can’t generate is genuine insight from real experience.

Programming content that offers unique perspective—hard-won lessons, counterintuitive findings, novel approaches—becomes more valuable in an AI-mediated landscape. The commodity content AI can produce competes with your commodity content. The insight AI can’t produce doesn’t face that competition.

The Actual Future

Based on current evidence, here’s what I expect:

Near Term (2026-2028)

AI coding tools become standard. Developers who don’t use them fall behind those who do—not because AI replaces work, but because it accelerates routine tasks. The productivity gap between AI-assisted and unassisted developers widens.

Junior developer hiring may decline as AI handles some entry-level tasks. But career paths don’t disappear—they reconfigure. Juniors who can effectively leverage AI tools remain valuable. Those who can’t face harder job markets.

Medium Term (2028-2032)

Some programming specializations face significant disruption. Work that’s primarily pattern implementation—certain web development, basic data processing, standard integrations—becomes more automated. Developers in these areas either move up the value chain or face displacement.

System design, architecture, and complex problem-solving remain human domains. The value premium for these skills increases as routine work is automated. The gap between “coder” and “software engineer” becomes more consequential.

Long Term (Beyond 2032)

Prediction becomes speculation. AI capability might plateau, leaving substantial human work. Or it might advance in unexpected ways, disrupting more than currently seems possible. Anyone claiming certainty about this timeline is overconfident.

What seems robust: software continues to grow in importance. The demand for people who can make software exist and work correctly doesn’t disappear even if “programming” as currently practiced transforms significantly. The job title might change; the need doesn’t.

What Programmers Should Do

Given this analysis, here’s practical guidance:

Embrace the Tools

AI coding tools are here. Refusing to use them doesn’t demonstrate superiority—it demonstrates inefficiency. Learn the tools. Understand their capabilities and limitations. Integrate them into your workflow where they help.

Effective AI use is itself a skill. Developers who can prompt effectively, evaluate AI output critically, and combine AI capabilities with human judgment will outperform those who either reject AI or accept it uncritically.

Move Up the Value Chain

If your work is primarily pattern implementation, you’re in the automation crosshairs. Deliberately develop skills that are harder to automate: system design, architecture, debugging complex systems, understanding users, navigating organizational complexity.

This doesn’t mean abandoning coding. It means positioning coding as one tool among many rather than the entire job. The developers who thrive will be those who can do what AI can’t—and use AI for what they shouldn’t waste time on.

Develop Judgment

The most valuable skill in an AI-augmented environment is judgment: knowing when AI output is trustworthy, when it isn’t, what to verify, and what to reject. This judgment develops through experience with both AI tools and fundamental software principles.

Don’t just accept AI suggestions—understand them. Don’t just reject AI limitations—learn to work within them. The programmer who understands both the tool and the domain makes better use of both.

Build Systems Knowledge

AI works on local context. Humans understand systems. Deep knowledge of how complex systems behave—distributed systems, security, performance at scale—remains beyond AI capability and essential for serious software work.

This systems knowledge compounds over a career. Each year adds understanding that AI doesn’t have and can’t easily acquire. The investment in fundamental knowledge pays returns that grow over time.

Maintain Human Skills

Communication, collaboration, negotiation, empathy—these human skills become relatively more important as technical execution is automated. A programmer who can only code competes with AI. A programmer who can code, communicate, and collaborate offers value AI can’t provide.

Mochi demonstrates these human skills daily, though in feline form. She communicates clearly (when food is required). She negotiates effectively (more treats than allocated). She collaborates when it suits her (sitting on my keyboard when I need to take breaks). Her job security is excellent.

The Honest Uncertainty

I’ve offered analysis and predictions, but honesty requires acknowledging uncertainty. I might be wrong. The optimistic case for programmers might reflect wishful thinking by someone whose livelihood depends on programming remaining valuable. The pessimistic case for AI might underestimate capabilities that will emerge.

What I’m confident about: the current discourse is too simplistic. Neither “AI will replace all programmers” nor “AI is just autocomplete” captures reality. The truth involves specific capabilities, specific limitations, and specific evolution of a profession that has always evolved.

The trajectory isn’t predetermined. How AI coding tools develop, how developers adapt, how organizations deploy these tools, how education evolves—all of these shape outcomes. Passive acceptance of any narrative is unwarranted.

Stay informed. Stay adaptive. Stay valuable by doing what’s valuable. That advice applies regardless of whether my specific predictions prove accurate.

Conclusion

Can AI replace programmers? The myth says yes, inevitably, soon. The reality says: it’s complicated, partial, and evolving.

AI can generate code. It can’t understand requirements, navigate tradeoffs, maintain systems, or solve novel problems. These gaps are fundamental to current AI approaches, not temporary limitations awaiting the next model release.

The programming profession will change—is already changing. Some work shifts to AI. Other work becomes more valuable as routine tasks are automated. The job transforms but doesn’t disappear.

For individual programmers, the path forward involves neither panic nor complacency. Use the tools where they help. Develop skills where they don’t. Build judgment about both. Position yourself for value that humans provide and AI doesn’t.

Mochi has observed this entire discussion with the detachment of a creature whose livelihood doesn’t depend on technological trends. She’s now sleeping on a warm laptop, demonstrating that some positions in life are remarkably secure. For the rest of us, the future requires more active navigation.

The question “Can AI replace programmers?” will continue generating clickbait headlines and anxious discussions. The answer will continue being: not simply, not completely, not soon—but also not never, and not without significant change to what “programmer” means.

That nuanced answer doesn’t make good headlines. It does reflect reality. And navigating reality, rather than headlines, is ultimately what matters.

The code you write tomorrow will probably involve AI assistance. It will also require human understanding, judgment, and skill. Both of those statements are likely to remain true for longer than the five-year predictions suggest.

Stay capable. Stay adaptive. Stay skeptical of simple narratives—including this one, which might be wrong in ways I can’t anticipate.

That’s the only honest advice for an uncertain future.